Throughout time, the Lake Roosevelt area has been a crossroads for the forces and desires of both nature and man.

Today, the area largely reflects the character and characteristics of human development and settlement over the past 150 years. With a closer look, however, one can appreciate a natural and cultural history as rich as any in America. This brief history merely touches the surface of why this area is so special.

For more literature, visit the Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area Administrative History, the Spokane Tribe of Indians, and the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation websites.

Sixty-five million years ago dinosaurs became extinct. Twenty to fifty million years ago, volcanoes spewed molten lava and tectonic shifts helped form mountainous areas in the Northwest.

Seventeen million years ago, some scientists believe a giant meteorite struck southeastern Oregon, causing floods of basalt lava. For a period of approximately four million years, lava spilled across the western lowlands and the Columbia Plateau began to form one of the largest basalt plateaus in the world. Indeed, 42,000 cubic miles of lava flooded the Northwest from present day Lake Roosevelt into Oregon. In some places, the basalt is more than two miles thick.

Lake Roosevelt sits on the northern edge of these flows. The lava filled valleys, turning eastern Washington from a land of hills and mountains into a great, flat plateau. Today, there are many places where layers of lava can still be seen.

About one million years ago, these volcanic fires were followed by the deep freeze of the ice age.

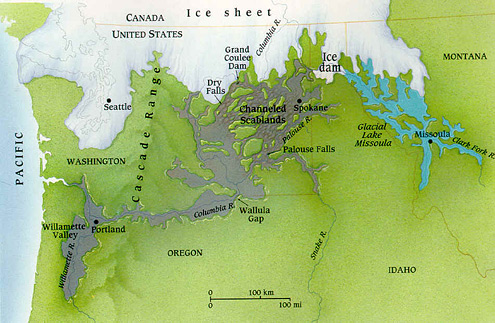

In Washington, these glaciers advanced down the western part of the Okanogan Valley about as far south as Chelan. In Idaho, a finger of the ice sheet came down to Sandpoint, where it blocked the mouth of the Clark-Fork River. In so doing, an ice dam almost one-half mile high was created.

This ice dam resulted in the creation of Lake Missoula, which was 2,000 feet deep and stretched eastward some 200 miles into Montana. Approximately the size of Lake Ontario and Lake Erie combined, the dam holding this vast inland sea first burst 15,000 years ago. Torrents of ice- and dirt- filled water rushed down the Columbia River toward the Pacific Ocean. The floods cut deep canyons, also called coulees, into the underlying bedrock. Over approximately 2,500 years, the cycle of nature creating an ice dam, forming of a lake behind the dam, the dam failing, and catastrophic flooding would repeat itself up to 70 times.

The floods carved out cubic mile after cubic mile of earth, forming deep channels and digging out riverless canyons such as Dry Coulee, Spring Coulee and Moses Coulee in a matter of days. And the floods widened and deepened the Grand Coulee to a depth of 900 feet.

These catastrophic floods and the formation of Glacial Lake Missoula are referred to as the Ice Age Floods. Learn more from the Ice Age Floods Institute, including how to drive the Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail.

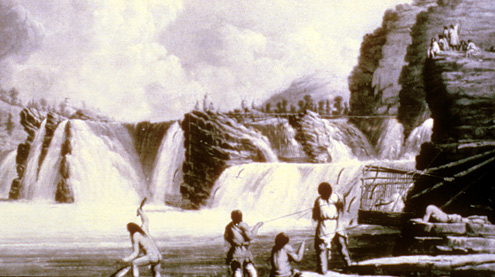

Indigenous peoples used Kettle Falls as a base for food gathering and fishing. The people of this period used the natural resources of laminated quartzite (for chopping) and black argillite (for small tools).

The Ksunku period began about 6000 years ago. Archaeological evidence shows them to be accomplished hunters of fish and wildlife, and gatherers of native plants. About 2000 years ago, the Salish speaking people came to Kettle Falls. Over a period of one thousand years, it’s believed that their numbers increased substantially.

The Shwayip period brings us up to the 19th century. Several tribes populated the area, moving their encampments to make best use of the seasons and resources at their disposal. The Spokane Tribe, for instance, dispersed their winter camps into smaller groups in the spring. By summer time, salmon fishing, hunting and root digging were central to their existence. Come fall, there was berry picking and intertribal social activities. By early winter, the smaller units regrouped to form winter camps along the river and creeks.

The Confederated Tribes of the Colville Indian Reservation relate a similar account of how their ancestors lived. They refer to their ancestors as “… nomadic: following the seasons and sources of food and moving from place to place to occupy fishing sites and to harvest berries and native plants. In their travels, our ancestors met other indigenous people of different speech and cultural practices.”

Fur traders, explorers and missionaries brought people of vastly different cultures to this area for the first time.

David Thompson, who was active in the fur trade, is the most well known early “explorer.” He arrived in Kettle Falls during salmon fishing season in 1811. He writes of tribal members with their “big woven baskets at the bottom of the falls (Kettle) … capturing fish.” His diaries talk of well constructed houses and he describes the village area as “a kind of general rendezvous for news, trade, and settling disputes, in which these villagers acted as arbitrators, never joining any war party.” By the beginning of July he was on his way down the Columbia looking for a trade route to the Pacific Ocean. He succeeded by making it to Fort Astoria and the Pacific Ocean. Learn more »

A year before Thompson, two men built a small trading post in 1810 at the confluence of the Spokane and Little Spokane Rivers. It was a small, crude cabin which they named Spokane House. This was the first permanent white settlement in what would become the state of Washington. Learn more »

By 1821, two of the largest trading companies, Hudson’s Bay Company and the Northwest Company, combined. The merged companies decided to build Fort Colvile near Kettle Falls in 1826. Fort Colvile was named after the British director of the Hudson’s Bay Company, Andrew Colvile.

As the influx of peoples continued, missionaries established themselves as well. Father DeSmet first visited Kettle Falls in 1841. By 1845, St. Paul’s Mission was built on a high point overlooking the falls. St. Paul’s Mission, which has an interpretive center, is open to the public.

The second half of the 1800s saw changes and influences to the area of ever increasing magnitude. Gold and other precious metals were discovered, the transcontinental railroad was built, and advertisements to farm the land brought more settlement. And with further settlement came new opportunities and increased conflict, struggle and sickness.

In 1853, the Washington territory was created. The first treaties between the U.S. government and Indian tribes came shortly after. As lands became more valuable, history saw the development of reservations where Indian tribes were often forcibly sent to live. By 1872, the Colville Indian Reservation was first created on its present location. In 1881, the Spokane Indian Reservation was created. Conflict and struggle was continuous for many.

Twelve distinct Indian tribes spanning distances from the Cascade mountains to Idaho were sent to live on the Colville reservation. They included the Colville, Lakes, San Poil-Nespelem, Southern Okanogan, Moses/Columbia, Wenatchi, Entiat, Chelan, Methow, Palus and the Chief Joseph band of the Nez Perce. Each had distinct cultures and were accustomed to a way of life that included migrating through thousands of square miles. In 1892, an act of Congress resulted in the north half of the Colville reservation being ceded and opened to settlement by non-Indians. Not until 1934 did Congress act to fully stop withdrawing of lands from the Colville Reservation.

One perspective is that of a relatively youthful nation coming of age in the world. Over the previous 130 years, America had grown from an agrarian society to one which used its wealth of natural resources and labor to embrace the industrial revolution. Westward expansion had brought America to the Pacific Ocean, the Civil War assured the union of the states, and World War I further established America as an international power.

A second perspective is one of poverty and uncertainty. With the stock market crash of 1929, droughts never experienced before and high unemployment, the 1930s were a time of crisis. In the Columbia Basin area, 40 percent of those that had come to till the soil had fled.

A new president, Franklin Roosevelt, announced a New Deal. Public works projects were developed to put America back to work again and invigorate investment in its resources. One of the largest and most ambitious projects was the building of Grand Coulee Dam. The first stakes were driven into the ground in 1933, and in 1935 Congress authorized the Columbia River Basin Project for irrigation, river regulation, power generation and other beneficial purposes. Its operations have grown to a size even beyond the imagination of those that first developed this extraordinary plan.

The economic benefits of the project are breathtaking. Over 670,000 acres of irrigation land with crops yielding a production value of over $3 billion annually; 6,800 megawatts of power capacity meets the needs of over four million residential customers annually; flood control saves billions of dollars in damage to downstream communities like Portland; and a National Recreation Area serving up to 1.5 million visitors a year.

These changes, however, also brought dramatic cultural and environmental shifts. With the building of Grand Coulee Dam, and then Chief Joseph Dam, salmon could no longer migrate to and from this area. The waters behind the dam rose 380 feet, inundating many tribal and non-tribal lands. Of particular cultural significance was the inundation of Kettle Falls, a focal point for catching salmon and social gatherings. For the Spokane Tribe, Spokane Falls played a similar role. Although not inundated, its place as a center of activity passed into history.

Mitigating the cultural and environmental consequences of development is an ongoing challenge. An exciting development is the Upper Columbia United Tribes working to reintroduce salmon into the upper Columbia River. Learn more »

Lake Roosevelt is currently managed cooperatively through an agreement among between the Bureau of Reclamation, the National Park Service, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the Colville Confederated Tribes and the Spokane Tribe of Indians.